The Black Lace Fan My Mother Gave Me by Eavan Boland

It was the first gift he ever gave her,

buying it for five francs in the Galeries

in pre-war Paris. It was stifling.

A starless drought made the nights stormy.

They stayed in the city for the summer.

They met in cafés. She was always early.

He was late. That evening he was later.

They wrapped the fan. He looked at his watch.

She looked down the Boulevard des Capucines.

She ordered more coffee. She stood up.

The streets were emptying. The heat was killing.

She thought the distance smelled of rain and lightning.

These are wild roses, appliquéd on silk by hand,

darkly picked, stitched boldly, quickly.

The rest is tortoiseshell and has the reticent,

clear patience of its element. It is

a worn-out, underwater bullion and it keeps,

even now, an inference of its violation.

The lace is overcast as if the weather

it opened for and offset had entered it.

The past is an empty café terrace.

An airless dusk before thunder. A man running.

And no way to know what happened then —

none at all — unless, of course, you improvise:

The blackbird on this first sultry morning,

in summer, finding buds, worms, fruit,

feels the heat. Suddenly she puts out her wing —

the whole, full, flirtatious span of it.

Eavan Boland’s death took us by surprise. She was so vital, so in charge, and only 75. We had a Zoom memorial for her two weeks ago. Hearing her poems read aloud by so many of her former students was a moving experience—the poems that she fashioned now have a new life in our voices. Although she died from a stroke at her home in Dublin, her death during this pandemic shook us. I’m grateful that I got to see Eavan last year at the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference. Here’s the introduction that I gave to her reading there:

“Do you remember when you first read a poem by Eavan Boland? What year was it, where were you, who were you then? I ask this question because if you can remember a time before Eavan’s poems, you realize how badly we all needed her books. I first read Eavan’s work in high school, call it 1991. I special-ordered a copy of Outside History, right when the Norton edition came out. My steady diet of Dickinson, Lowell, Plath and Sexton, supplemented with Walcott and Heaney, was deficient. I got the hardback copy with the purple-black cover, a vase of lilacs on the cover.

To read those poems was to feel comfort—yes, this is what I’d been looking for—but it was also to feel terror—Boland’s poems were difficult, unflinching. They did not give you what you wanted.

In one of her most popular, break-out poems, this one first published in the New Yorker back in 1987, “The Black Lace Fan My Mother Gave Me,” a daughter is handed a gift which dates from her father’s courtship of her mother. After a detailed, curatorial, ekphrastic description, Boland decides to liberate the fan from its status as nostalgic object. It is alive, a blackbird’s wing in flight. Boland’s poems begin with what is there in front of us—the ordinary ancestor, some domestic archaeology of children’s toys, teacups and saucers—and after extending a respectful and somewhat deceptive homage to the object or ancestor, her poems systematically, painstakingly, and without any trace of sentimental, completely transform what we thought we knew in the world.

We have our fore-mothers, their mistakes and their coups, and to be female was to have time embedded into you. Boland’s poems made that all ok for me. The presence of Boland’s work is so foundational, I can’t imagine a time without it. It’s hard to imagine Mark Doty, Natasha Trethewey, or Maeve McGuckian without Boland’s example.

Reading Boland before I knew her, I began to realize there was place for girls in the canon, that with her work Boland was ripping open a seam where we could slip in. Girl-poets need not be troubled or overly dramatic to purchase a place for ourselves. In her aesthetic, as we read her now, understatement is a value; it’s the not-said, some mystery that will not be wrapped up in neat politicks. How important it is now to look at the syntax of her work, the re-ordering of the world.

To see how the sentimental is transformed into the numinous.

When I ended up at Stanford in 2001, grateful beyond belief to be her student, one of her great aims was to warn us young poets off of the precious. I realize now, in her exhortations to steel ourselves against sentimentality, she was trying to inoculate us against smallness. This was a way out she’d found, and she offered it to us.

Prompt: Take an object from your parents’ past and fashion something from it. Remember that Yusef Komuynakaa poem, “My Father’s Love Letters?” Or, take a few minutes and write a few paragraphs about a poet who has influenced you. Why did they mean something to you? We grow as poets not just from writing poems but from considering our own sensibilities and how we’ve developed them, as I’ve said before.

Journal: The Irish Pages, a Belfast literary journal edited by Chris Agee. When I was a Fulbright professor at Queen’s University back in 2010, I got to meet Chris and learn about his amazing advocacy for Northern Irish poets.

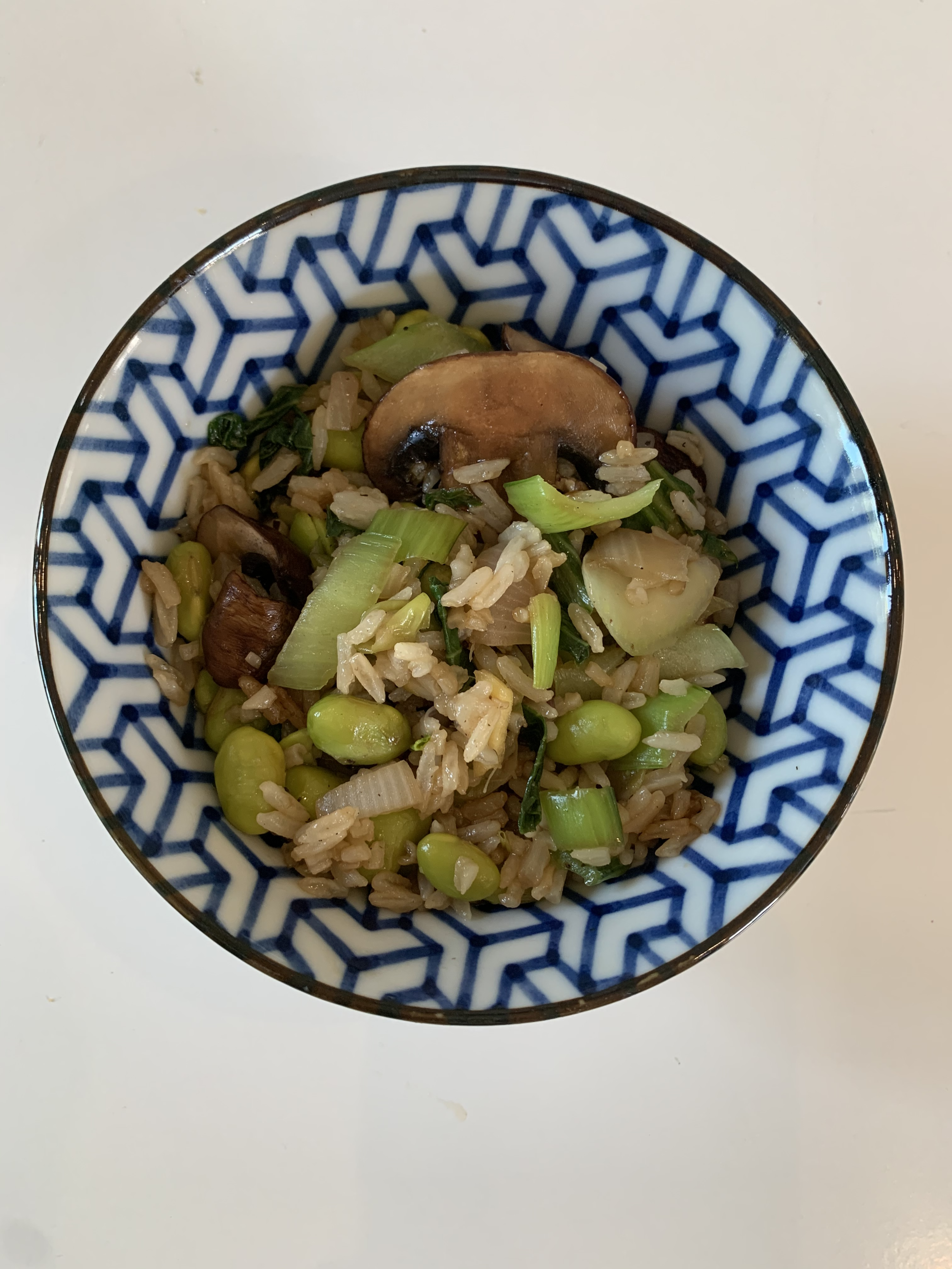

Recipe: Gingery Fried Rice with Bok Choy. This is another great brunch/lunch recipe that is even better cold on Day 2 or 3.

Enjoy your Memorial Day weekend, everyone!