from “Soap,” by Francis Ponge

There is so much to say about soap. Precisely everything that it tells about itself until the complete disappearance, the exhaustion of the subject. This is just the object suited to me.

*

Soap has much to say. May it say it with volubility, enthusiasm. When it has finished saying it, it no longer is.

*

Soap was made by man for his body’s use, yet it does not willingly attend him. This inert stone is nearly as hard to hold as a fish. See it slip from me and like a frog dive into the basin again … emitting also at its own expense a blue cloud of evanescence, of confusion.

*

For a piece of soap the principal virtues are enthusiasm and volubility. At any rate ease of elocution. This, which is excessively simple, has nonetheless never been said. Even by the specialist in commercial publicity. And what do the soap-manufacturers offer me—not a penny! They have never even thought of it! Yet soap and I will show them what we can do …

*

There is nothing in nature comparable to soap. No stone is so modest nor, at the same time, so magnificent.

To be frank, there is something adorable about its personality. Its behavior is inimitable.

It begins with perfect reserve.

Soap displays at first perfect self-control, though more or less discreetly scented. Then, as soon as one occupies oneself with it, I won’t say fire, of course, but what magnificent élan! What utter enthusiasm in the gift of itself! What generosity! What volubility, almost inexhaustible, unimaginable!

One may, besides, soon be done with it, yet this adventure, this brief encounter leaves you—this is what it is sublime—with hands as clean as you’ve ever had.

*

Because of this object’s qualities I must expatiate a little, make it froth before your eyes.

*

Violent desire to wash one’s hands.

Dear reader, I suppose that you sometimes want to wash your hands?

For your intellectual toilet, reader, here is a text on soap.

*

This egg, this flat

dab—this little

almond, which

grows so quickly

(almost instantly)

into a Chinese fish

With its veils and kimonos

And wide sleeves

Thus it celebrates its marriage

with water. Such is the gown of its marriage with water.

*

One would never be through,

with soap!

… Yet it is necessary to return it to its saucer, to its strict appearance, its austere oval, its dry patience, and its power to serve again.

trans. by Lane Dunlop in the Paris Review

Craft Musing & Prompt:

We’ve been thinking a lot about soap lately! I remembered the Francis Ponge poem and started reading Ponge in an attempt to revive the simple objects in our homes that we’ve been staring at for a bit too long here on Day 956, 623, 444 of the pandemic.

Robert Bly calls prose poems “the natural speech of a democratic language.” Robert Hass calls his prose poems a long escape. He’s said he wanted to write prose poems which didn’t sound like prose poems. And remember what Frank O’Hara writes: “ It is even in prose/ I am a real poet.” I have a friend who dumps his poems into paragraphs, then looks for the line breaks in the language of the paragraph. Other poets settle on vision of line breaks and build their poems around that.

Whatever you’ve been doing, however you’ve been building your poems, your assignment for today is to build a poem the other way. Throw the lines of a poem into a paragraph and break them in a different place. Or, challenge yourself to write a prose poem. Here are some more Francis Ponge poems on the very excellent Pen America website. (That’s your journal of the day. My kids are running wildly through the house and I’ve got to finish this entry!)

Here’s a PDF of an entire Ponge translation. Download and scroll to page 40 for his “Methods” manuscript where Ponge outlines the thinking behind his poems. I think you’ll find his prose style as engaging as I do.

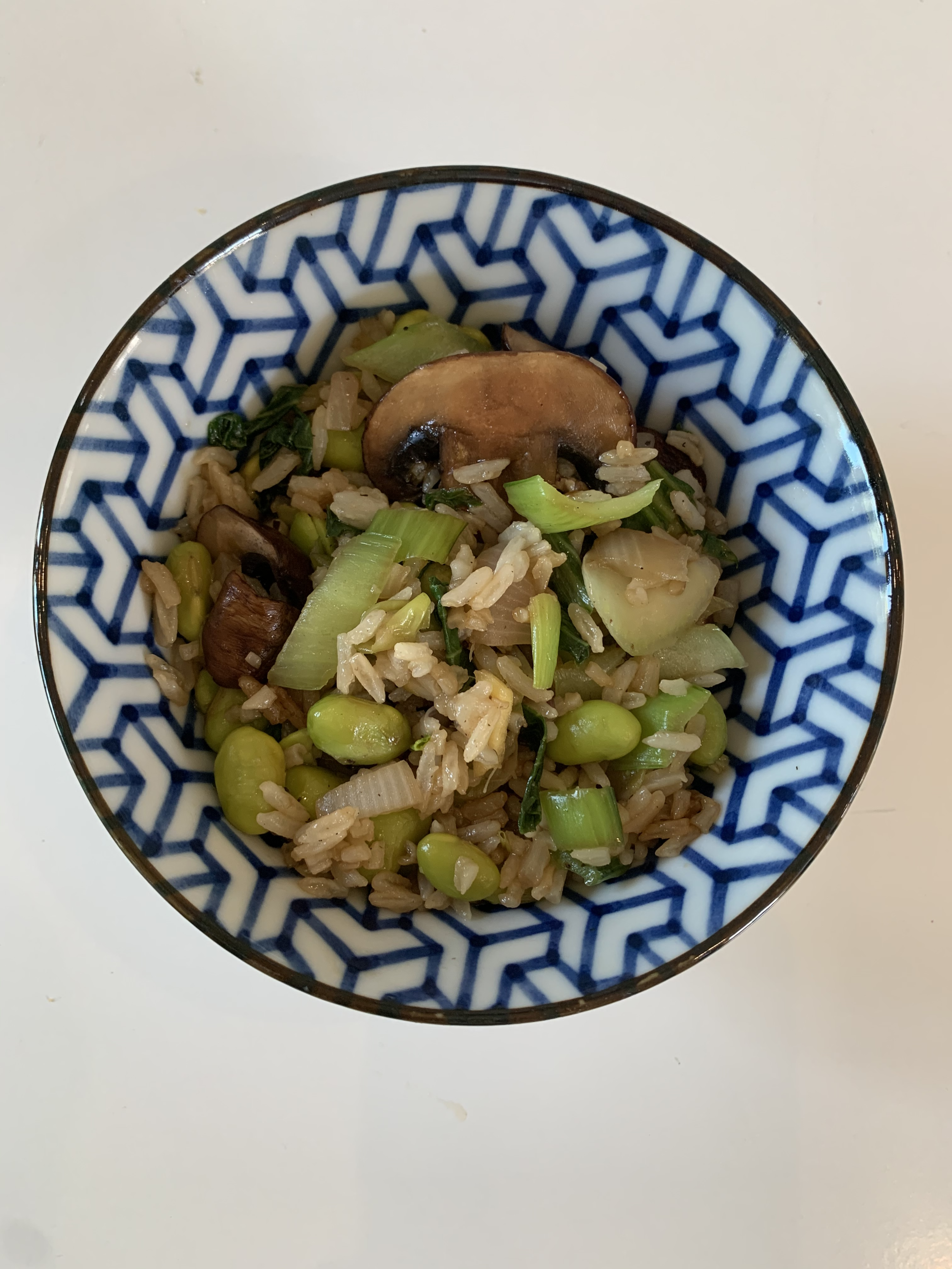

We’re in intimate connection with our domestic worlds these days. It’s a good artistic practice to “take the side of things” and look at our forks and salt shakers and chairs in new ways.

My friend at Reveal was finalist for the Pulizter Prize this month! I made her a cocktail called “The Journalist,” poured it into a Mason jar, and took it to her front porch yesterday evening.

Finally, a plug for a tiny company making bars of soap & shampoo. A 6th grader and a high school student are making it in their kitchen. Gorgeous, package-free eco bars made in Albany, CA. Sustainabar.

This is my last blog entry. Special thanks to my brother in law Patrick Kelly and friend Lane Greene for the great photos! And to Francis Kelly for helping me get the hang of Squarespace. Looking forward to seeing you on the other side, beautiful poets!